Still On track: 160 years of the railways in Sandhurst & Bendigo

The importance of rail infrastructure in Australian history can never be over stated, the capacity to move people and commodities for all sorts of reasons – commerce, warfare, infrastructure and pleasure was instrumental in building community and culture across Victoria. In October 2022, the 160th anniversary of the opening of the Melbourne to Bendigo railway line will be observed and BRAC have chosen to explore our collection for items that can shed a light on the human stories around the beginning and growth of the railway, both in this article and a month-long exhibition upstairs in the Bendigo Library.

Rather than focus on the vast detail of the engines, the workshops and other infrastructure, we’ll be looking instead at three lesser-thought of elements of the Bendigo Railway Station which tell us about the people involved and the interaction between rail and the local community – the Stationmaster’s House, the Victorian Railways Institute, and the Refreshment Rooms. At the heart of any big industry is its people, and rail is no different.

To download the article as a PDF, click HERE.

Celebrations: Opening and a Century Later

In October 1862, after several false starts, a grand opening day for the Melbourne Sandhurst Line arrived. The Cornish & Bruce company had been awarded the tender to build the Melbourne, Mt Alexander & Murray Railway Line in 1858 and on 12 October 1862, the Cornish became the first train to pass the Municipal District of Sandhurst’s boundary. The construction was said to have involved more than 422 stonecutters and masons, 125 blacksmiths and 190 carpenters.

There had been some discontent between the Bendigo and Castlemaine councils about where and when the official opening and the Municipal Borough of Sandhurst minute books record some of the deputations that went back and forth, trying to secure a firm plan. When the groups were unable to agree, Councillor Casey took the matter higher, approaching the Minister for Railways directly. Eight days later, on Monday 20 October 1862, the official opening took place – in Bendigo – with brilliant spring weather and Victorian Governor Sir Henry Barkly with Lady Anne the special guests.

[TRANSCRIPTION]

Oct 6th 1862

Committee Macartney, Jackson, Holdsworth & O’Keefe

Special meeting to receive report of a committee on railway opening celebrations who had met a committee of the Castlemaine Council in same respect. Cr Casey reported on behalf of himself and colleagues (Cr Burrowes and O’Keefe) that no arrangements could be made with Castlemaine. On motion Cr O’Keefe, it was unanimously voted to send Cr Casey as a deposition to Mitchell to make if possible final arrangements in respect of the opening

Confirmed - Robert Burrowes, Chairman

Flags, wreaths and bunting were in abundance in the surrounding streets which were soon thronged with people in their best holiday clothes. The Victorian Cavalry, under the watch of Captain Bastard, paraded in preparation for their guard of honour. The fire brigade members, and fully-kilted Caledonian Society members joined the parade. A bullock roast for spectators was well under way – the beast having been put on the spit on the Sunday night – for eating with bread and cheese, and ale.

The first train arrived just before one in the afternoon, carrying passengers from the Castlemaine district, and the Melbourne train with the Governor, his entourage and 500 visitors pulled in half an hour later. First, His Excellency spoke with the railway workers, gathered for a large feast on the hill behind the station, and then got into his carriage, drawn by four local grey horses, and after giving an address from the balcony of the Criterion Hotel, headed for the Town Hall.

Here, a banquet had been laid out for 800 guests with ‘every delicacy, even ice’, gracing the tables. The darling of the social set, pineapples, were the notable absence but they – along with a great deal of crockery – had been destroyed in a goods train crash at Woodend. Seated were politicians, clergymen of different denominations, railway magnates, doctors – homeopathic and allopathic – and local celebrities, ‘all loving and loathing each other’.

It was estimated that between 15,000 and 20,000 people took part in the celebrations across the day. In his toast, the Governor noted that he felt more pleasure on this occasion than before, having not arrived ‘heated, dusty and weather stained, having been jolted over rough roads and boggy holes’, one so notorious the locals called it the Bay of Biscay. Guests numbering 1,300 later gathered for a ball, women reviving the old aristocratic French trends of powdered hair in a ‘galaxy of beauty and fashion’.

The construction had not gone without its disasters, including the death of a breaksman on a section of the line south of Bendigo. The coroner determined that George Warde came to his death at the Big Hill Railway Tunnel accidently from the effect of severe injuries received by the passing over him of a railway waggon [historical spelling] whilst he was acting in the capacity of breaksman and that had he put the break on the last waggon, his death would not have occurred. He then recommended to the railway authorities that steps should be taken to see that gangers give proper instructions on the use of proper appliances to prevent further accidents.

There are a significant number of letters in both the 19th and 20th century Inward Correspondence collections for the City of Sandhurst-Bendigo which relate to the railways, including letters from Victoria Railways and even the Victorian Railways Military Band. Some have very decorative letterheads and safety awareness campaign stickers, like these:

City of Bendigo, Inward Correspondence, 1927

A centenary celebration for the opening of the railway was held in October 1962 and included an exhibition in the basement of the City Hall and the arrival of the ‘Centenary Train’ at the station with 300 members of the Australian Railway Historical Society on board. The Bendigo Mayor, Cr Rae, unveiled a commemorative plaque to acknowledge the occasion. “Today is a day of memorial thanksgiving in Bendigo when we remember the pioneers who toiled to lay this important link with the country and city,” said local MLA, Bill Galvin. Present at the event was Harold Curnow, great grandson of Dr Cruikshank who served as railways medical officer during the construction before serving as the District Health Officer for Bendigo. The Doctor had been at the initial ceremony to celebrate the opening of the line.

The exhibition featured photographs, artifacts and documents, including an 1888 rail ticket, a VR (Victorian Railways) Free Pass Medallion from 1879, and a combined walking stick-rail gauge. Also on display was the Challenge Shield, presented to the Victorian Railway Ambulance Corps in 1911 for an annual competition in the application of first aid, which had been won the previous three years by the Bendigo North Workshops team.

Just three years later, just before Christmas, a fire broke out in the Refreshment Room and the complex, including the original 1863 station on the Quarry Hill side of the track, was destroyed. It took some time for a signal box to raise the alarm and the staff were able to rescue equipment – and the parcel office with its contents. The equipment included a 100-line automatic telephone exchange and a £20,000 teleprinter. Another fire broke out from the roof of a gutted building while salvage operations were underway. It was said to be second only in size to the biggest fire Bendigo had seen, just three years before when the Bendigo Advertiser building went up in smoke. Station Officer Vin Lapsley fell 15’ while trying to extinguish the fire but remarkably survived the fall, and blazing timber fell among the other men doing their best with poor water pressure.

While no one was killed in the fire, up until 1984, over 80 inquests have been held in relation to deaths which have occurred in connection to trains, stations and gatehouses, including several staff engaged in shunting operations in the 19th century. These inquests are all available through the PROV catalogue and those up to 1937 have been digitised and can be viewed or downloaded direct from the site.

By 1979 the station was handling 82,000 passenger journeys per year, and it remains an integral part of the V/Line network to the current day, with stations north of the Bendigo line reopening to encompass the growing city, including Goornong and Epsom.

Care For a Cuppa? The Bendigo Refreshment Rooms

Ensuring weary travellers could find refreshment through a meal and a drink was a pivotal function of railway stations when journeys were a great deal longer and stops less frequent. Refreshment Rooms became the answer, with facilities as small as a bar and as grand as a full-service dining room soon added to each station. Initially they were leased out to suitable candidates on two-to-five year contracts, and the management of the Room in its entirety was down to the lease holder, from staffing to supplies, to liquor licences and health regulation compliance.

The first operators were Martin & Honner, who advertised themselves as ‘Caterers under the Victorian Government’ and promised that ‘excursionists and the travelling public generally will find every convenience in the shape of tea, coffee, chops, steaks, wines, spirits etc of the best quality promptly and carefully supplied at and before the starting of every train.’

In Bendigo’s case, the Refreshment Room managers were often professionals in this particular catering space, and there was a great deal of churn between stations. Herman Alvater arrived in 1880 from managing the Deniliquin and Moama rooms; he took over from Septimus Durrant, who in turn was on his way to Ballarat Western station. After Alvater’s departure in 1883, following the death of his wife Ellen, former chemist William Stembel took over the lease and remained there for almost a decade.

Public Record Office Victoria – Victorian Railways VPRS 12903 Photographic Negatives: Railways: Box Systems

The time was not without trouble however, with Inspector Rattray charging Stembel with breach of the Health Act when he was sold ‘reduced’ whisky. His son, barman George Stembel and barmaid Miss Hannan told the court that they were responsible for the mix up and no penalty was laid. The business of running the Refreshment Rooms seems to have been a family one throughout, with later managers, including Henry de Groot, Annie Scully an Edward Ingham, engaging relatives to work as barmen, cleaners, waitresses and cashiers.

Under the operation of Archer & Day in the late 1890s, the licencing court awarded the Refreshment Rooms the right to extend their operating hours from 4:30AM to midnight so that they might accommodate passengers on the early and late trains. After the Rooms were taken over by Henry de Groot, we see an entry in the Golden Square Licencing District record of a transfer for the licence from Day to de Groot approved. He had good reason to ensure one of the most profitable parts of the business continued – he had paid the Department the modern equivalent of $260,000 for the rights to cater the Kyneton, Castlemaine and Bendigo Rooms for two years.

VPRS 1437 Bendigo Courts Licencing Register 1897

A new leasing system, based on five-year contracts, was launched in 1904, and Annie Scully from Korong Vale near Wedderburn transferred to Bendigo, though Mrs de Groot appeared to continue to work there, opening up in 1907 to find that thieves had broken in through the ladies’ waiting room, but failed to find any money to steal. Prior the Great War, the lease was later transferred to well-known Woodend proprietor, Elizabeth Hemming.

The Railways Department eventually took control of all Refreshment Rooms, finding that their ability to operate economies of scale across the multiple outlets led to reasonable profit. It also gave them greater control over the passenger experience, hoping to avoid feedback such as this letter to the editor:

“The refreshments are altogether bad and the service is abominable. It is bad, worse and worst. Ballarat is the vilest of them all, though it must be conceded that Kyneton and Euroa are bad enough. These remarks do not apply to the Sandhurst station where the good liquor and attendance is all any reasonable person could desire and commercial travellers look forward to Mr Alvator’s as the only place where they can get a good meal decently served.’

In Bendigo, the Rooms were brought under the Department in June 1919 and by this time the whole system of railways was essentially self-sufficient, with engineers, workshops and even a power station. The Chief Commissioner set up the Refreshment Services Branch and by 1926, there were 61 Rooms operating across Victoria, employing 770 people, with well over half women in waitressing, bar staff and laundress roles, all working under the motto, ‘Service in order to obtain satisfied guests’.

At this time, the Railway Refreshment Rooms, or RRR as they were collectively known, was supplying over 3.25 million meals each year, including 33 ton of meat. By 1970, the meat order had exploded to over 360 ton! The Railway Refreshment Rooms contributed to various campaigns, including the Milk Board’s ‘Drink More Milk’ campaign in the late 1930s which significantly increased demand for dairy based drinks in Refreshment Rooms and dining cars. The first request to the Railways Commissioners to promote milk in their stalls and rooms came from the Women’s Christian Temperance Union who wished more people to drink milk instead of liquor.

Sample Railway Refreshment Room menu c late 1960s

Meat Pie & Sauce 25c

Sausages & mash NA

Curry & rice 75c

Steak & kidney 75c

Apple pie & cream 22c

Tea or coffee & milk 13c

Fruit cake NA

Assorted biscuits 22c

Assorted sandwiches NA

Scones & Butter NA

Public Record Office Victoria, VPRS 12800 Photographic Collection: Railway Negatives: Alpha-numeric Systems

Edward and Cora Ingham managed the Bendigo rooms throughout this early period, including during the promotion of fresh and dried fruit to support soldier settlers in the citrus industry. After the ‘Every day in every way’ campaign initially launched, the railways bakery was producing almost 160 loaves of raisin bread per day, and by 1924, production near 1,000 per day. Cora was the first occupant of the Refreshment Rooms to be listed as ‘manageress’ in the Victorian electoral roll. The next was Elsa Rubeo, who with her husband Alfred (both pictured in black, below), operated the rooms into the 1930s. By this time many time-saving appliances had been introduced, including a steam heated cabinet for keeping ‘crockery and dainty dishes’ hot.

Perhaps some of the women pictured in this platform photo were those who held a meeting four years earlier to decide against taking part in a general strike by all Victorian Railways waitresses. In 1925, a confidential report written by Capt Oswald Carter, Inspector of Railways Refreshment Rooms, was leaked. In the report, he noted that three particular waitresses at one Mallee station were ‘dirty, lazy and unmanageable, and should be replaced’. The Railways Union conveyed select parts of this report to waitresses in the metropolitan area, and 90 of them went on strike, demanding an apology from Carter.

Museums Victoria, MM 4048, Bendigo Refreshment Room Staff 1929

Soon, the women discovered that they had not been given all of the facts – that Carter was referring only to three specific waitresses who had been replaced, and had in fact reported that work at the other rooms was exemplary. A group attended Unity Hall to tell union leaders that if the facts had been made clear to them in the first place, they would never have stopped work. They were hooted, and charged with breaking the strike. One official accosted a girl in the lobby and called her a black leg; in response, she ‘boxed the man’s ears’, reiterating that they had been misled. The Bendigo waitresses had determined early that Carter’s statement did not apply to them and continued their duties – joined by an extra six girls to help with the increased demand from passengers coming to the Bendigo Football Club semi-finals.

In 1934, instructions were issued to James and Constance Corkhill, then joint managers of the Rooms, that luncheon and dinner menus should include soup, fish or entrée, joint (roast), pudding, green salad, bread, butter, dry biscuits, cheese, tea, coffee and milk, and two-to-three varieties of fresh fruit, and poultry at least twice a week.

An instruction booklet was also distributed to Refreshment Room inspectors, who were bound to regularly visit each station, including Bendigo, and where required provide instruction to the Managers. He would be responsible for the recording and accounting of supplies, hygienic handling of food, appearance of the manager and staff, and delivery of ‘prompt and attractive service’ to passengers. They were required to check and record the tapes in cash registers, to ensure that electro plate cleaning was done thoroughly and safely, to inspect plants used as table centres for health and suitability, and the quality of liquor and food supplied from local businesses, including dairies.

They were to be familiar with the Factory Regulations, Health Regulations, Arbitration or Wages Court Determinations and the Licencing Act. The page depicted left from a VR Dietitian’s Book records the analysis of milk collected at various points on the Bendigo line, which unlike bakery, poultry and meat products, was all sourced locally.

The Refreshment Room was the ignition point for the fire which razed the original, 100-year-old station building in 1965, with images like those shown above and below in PROV’s Railway Negatives collection the only reminder of the grandeur of the Bendigo Refreshment Rooms and the scale of the old kitchens.

VPRS13419 P0001 1 – Dietitian book (Bendigo), noting the quality tests done on milk supplied by local companies, including BCC and the Hollywood Dairy

Public Record Office Victoria – Victorian Railways VPRS 12903 Photographic Negatives: Railways: Box Systems

At Home With the Boss: The Stationmaster’s House

The railway yard was a hive of activity and employed a significant range of staff, from waitresses to engineers, telephonists to blacksmiths, gangers to conductors, and firemen to porters. All were under the oversight of the Stationmaster, an appointment made directly by the Railways Commissioners. Nineteen individuals served in the role between the opening of the station in 1862 and 1935, including three who died at their post, and several who lived at the station – from 1877 in a specific Stationmaster’s house built by the Department of Railways & Roads.

The inaugural Stationmaster, in harness for just a year, was Henry Masters Barter, an Irishman by birth who had been transferred with his wife Margaret and daughters Elizabeth, Teresa, Anna and Margaret, from Werribee. He was assisted by Ball and Montgomery, and after his first twelve months of setting up the station, was promoted to the Melbourne Station to perform the duties of Stationmaster.

The next man, who oversaw the introduction of the Sandhurst-Echuca service, was William Cameron, a Scot who took an active part in Bendigo life before being farewelled in 1865. John Anderson came next, a former Castlemaine stationmaster who had joined the railways after finding that, due to a speech impediment, he would be unable to rise to the rank of captain of the Cunard line of ships he had initially worked on. Anderson, as well as his successor, John O’Malley, all went on to take senior roles at the Melbourne terminus – it seems Sandhurst was something of a training ground for the ‘big time’.

VPRS 17077 Contract Files – Department of Railways & Roads P0001 8

For nearly two decades, the station would then be under the control of William Ramsay – another Scot – who, seven years into his tenure, would move into a brand new Stationmaster’s house, leaving the previous apartments to be used for public accommodation. Here, with his wife Isabella, who served as honorary secretary for the Industrial School, they raised a family of ten. The contract for ‘the erection of brick residence for the Stationmaster at Sandhurst’ was issued in August 1877, awarded to Castlemaine builder, Isaac Summerland, who had also built the passenger stations on the Sandhurst, Eaglehawk, Bridgewater and Inglewood lines. The works came in at a total cost of £1,800, below is part of the final return, lodged in 1878. The final Schedule of Prices, outlining the fine detail of the specifications – including the use of British Bangor slates and exposed bluestone needing to be cleaned with spirits of salts – ran to over 40 pages!

Ramsay had started his career as a booking clerk at the Edinburgh Railway Station and once in Australia, worked at the Sunbury, Kyneton and Castlemaine stations. Tragically, his son William, a clerk at the Bank of Victoria in Bendigo, drowned in 1875 while bathing in the Campaspe River. Ramsay fell ill in 1887, and the newspaper noted they hoped that along with his return, a ‘change in the politeness on the part of the porters’ would follow. The following year, at the age of 60, he retired to Hawthorn and the Maryborough Stationmaster, John Franks, took his place – the first in a long line of Stationmasters to record a very short tenure.

Two years later, Isaac Chapman took the post but was soon taken with an attack of what was thought to be eczema, which apparently had afflicted both Franks and Ramsay. His illness developed and after suffering for some time, opted to retire to Geelong, where it was hoped the change of air would aid his recovery. Next, William Sinclair and his family moved into the brick residence. After two years in the job, in April 1893, the eldest Sinclair daughter, Mabel – who had in 1888 rescued a fellow teenager from drowning – succumbed to illness. As a reportable disease, her death of typhoid fever was recorded in the quarterly Health Officer’s report to the City of Bendigo which would have been forwarded to the Board of Health. She was one of 17 Bendigonians to die with the disease in that three month period, including four members of the Cheesewright family.

VPRS 17077 Contract Files – Department of Railways & Roads P0001 8

Later that same month, the Railways informed Sinclair of their intention to retrench him at the end of June. A sale of the family’s furniture was held at the Stationmaster’s residence and he retired, with Maria, to Melbourne. The family had reason to return however, first in 1898 when 20-year-old Victor died and again 1900 when their 23-year-old daughter Victoria died, with both being interred with their sister Mabel at the Bendigo Cemetery. Both William and then Maria would similarly be returned to Bendigo for burial after the Great War.

Through the early part of the century, David Walker, Simon Smith and Joseph Yates managed the station. Romance blossomed for Yates, who married Amelia, the daughter of the Refreshment Room manager, William Stembel, with six children to follow. He had previously worked at Stawell and Wodonga, and had relieved at Bendigo from time to time. Despite being under the care of Dr Rockett for ongoing ill health, Yates died suddenly after a heart attack, leaving the station without a master.

His replacement met a similar, unfortunate end. Seven years after his appointment, John Taylor who had started as a junior clerk at the Williamstown depot, was advised to seek a change of air, but the approach was unsuccessful and like his predecessor Yates, died suddenly from ‘the exertion of climbing the hill in Forest street’. Unlike Yates and Sinclair, Taylor was taken to Melbourne for burial.

A further run of short appointments followed – William Noonan, Daniel Brown (who resigned after a ‘health breakdown’), James Brown, John Kenny, and then in 1923, Michael McCraith. The bachelor McCraith had worked for the railways for a number of years and in 1930, announced his retirement, looking forward to an extended holiday which would include America, the Continent and England for several test matches. The week after his going away party at the Station, McCraith also died. His will named as beneficiaries St Aiden’s Orphanage, the Sacred Heart Cathedral Choir and the St Patrick’s Sports Committee, among others. The railway staff made a presentation of a new bed to the Bendigo Hospital’s male surgical ward in his memory.

Reginal Buck, Charles Wadelton, Albert Giles – with his clock inscribed ‘Courtesy costs nothing. Its cultivation is invaluable to all of us’ – and William Russell, who was not permitted to meet Queen Elizabeth at the station when they arrived in Bendigo due to his nephew having died of polio the previous week.

A long list of occupations relating to the Railways can be found in the City of Sandhurst-Bendigo rate books, including porters, gaugers, labourers, carriers, agents, guards, managers, inspectors, gate keepers, traffic superintendents, fitters, blacksmiths, firemen, carpenters, engineers, foremen, clerks, drivers, cleaners, repairers, signalmen and plate layers. In many cases, these match up neatly with the Railway employment lists produced in the Victorian Government Gazettes. These lists also include details of which department the individual was employed within, and the date they started working with the railways.

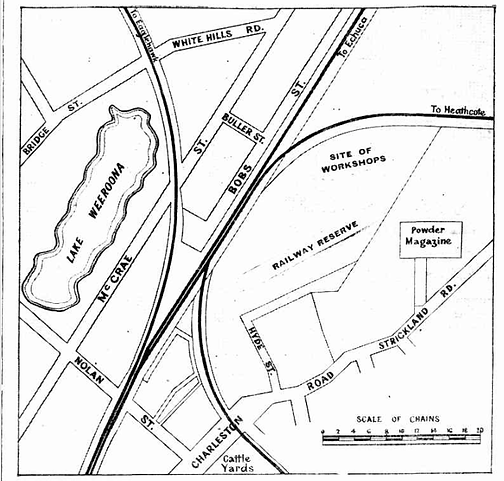

It is easy to spot a pattern of residency for these staff – enclaves existed in the Olinda, Gladstone and Russell street areas, the Garsed, King and Queen streets area, and naturally, the Railway Reserve (between Strickland Road and Lake Weeroona).

The families of staff tended to work in with the local community, no matter how short their stay was. Their children attended the schools, sons competed in sports teams, and wives and daughters engaged in philanthropy. This was especially true during the Great War. John Laffan was a roadmaster – the man responsible for the fixed infrastructure of a given line – tracks, bridges etc – and the family had moved first to Eaglehawk from Korong in 1908.

The Laffan family had a close association to the railways with John Snr employed in the trade, as well as several of his brothers, and indeed one of his sons, John Michael, becoming a junior field clerk. Other distant cousins were guards and gangers, and another a fireman who had the misfortune of finding his two sisters dead in a carriage after a major crash in 1908.

During the war, a popular way to raise funds was through Queens competitions. Various parts of the community would put up a ‘Queen’ who would represent them in various fundraising activities over a set time, with the crown being bestowed upon the young woman who raised the most money for the war effort and the most votes from the public. The Laffan girls were quite sharp, Mollie and Eileen both winning prizes at their St Mary’s College for French, English, deportment and physical culture; Eileen gained distinctions in arithmetic and geography. Perhaps this contributed to the decision in 1916 to appoint her as the face of industry as ‘Queen of Railways’, along with the fact that her older brother John Jnr, was serving with the Field Company engineers in France.

With the help of her and other railway families, she held several euchre parties and dances and a stall at St Joseph’s school, in the ‘team’ colours of red, white and blue. Even a ‘men’s coterie’, including future Stationmaster John Kenny, assisted in the delivery of over 30 ‘entertainments’ resulting in over £335 raised by the Queen of Railways to polling more than 80,400 votes.

Despite leading the competition into the spring, at the Coronation ceremony at the Lyric Theatre, the Queen of Australia, Irene Dorrity, ultimately took the crown, with Eileen in a creditable second place. Overall the girls managed to raise £2,000 (around $215,000 in modern terms). As the war ended, Laffan took up the roadmaster’s position at Newmarket and the family moved again, to Melbourne.

PROV’s collection of inquest deposition files give us insight into the dangers of working on the railways, with many of the 80 inquests related to Bendigo railway deaths up to 1980 being for staff. Many more were injured, often in shunting accidents but gate keepers too were subject to injury and fatality despite their familiarity with the job. In 1913, the Victoria Street gate keeper at Eaglehawk, Jane Morris, was hit by a special ballast train bound for Raywood. Two school children had witnessed Mrs Morris come from her house to open the gates after the warning whistle sounded but the fast moving train arrived too soon and clipped the old woman. The collision was unnoticed by the driver, Denis Mangan, nor his fireman Owen Donohue or guard Edward Evans. As a result, Mrs Morris was dragged along the tracks a further 40 yards before another member of staff, William Knight, raised the alarm at Eaglehawk station. John Laffan conducted an inquiry in addition to the inquest held at the nearby Railway Hotel, but it was found that the death was a result of an accident.

For other inquests, including those for Martin Meaney, jammed between buffers in 1883, Walter Cockburn, who fell from a buffer in 1890 and Herbert McKean, who was crushed by a rail truck in 1920, search ‘railway AND Sandhurst’ in PROV’s catalogue, limit the results by ‘Inquest deposition files’ and ‘online’ files and you can view full digital copies of the witness depositions, jury lists and more.

Pursuing Personal & Professional Growth: The Victorian Railways Institute in Bendigo

One of the biggest social clubs in Victoria, by 1961 the Victorian Railway Institute had over 17,000 members and operated out of purpose-built halls across the state. Bendigo was the second country branch opened after Ballarat, and offered educational and recreational opportunities to the many staff of the Victorian Railways.

Public Record Office Victoria – Victorian Railways VPRS 12903 Photographic Negatives: Railways: Box Systems

The first meeting of the Bendigo VRI was held in 1913 but due to embargoes on infrastructure builds, the Hall – designed by the Railway’s own architect, James Fawcett, and still in situ today – was not opened until 1924. For the official opening, Railways Commissioner Miscamble joined the VRI committee in the ribbon cutting. A group of musicians from the Melbourne VRI presented a concert for the occasion and the building and gardens were made available for inspection. The Bendigo Advertiser described:

‘It is built of brick and cement mortar, a main hall is well lighted and ventilated and may be divided into three sections by use of three sliding partitions. Two of these are intended for use as classrooms and the third as a committee room. There is a billiard room, a cloak room, kitchen and library, all tastefully furnished and Marseilles tile used on the roof.’

Bendigo Advertiser, 14 Apr 1924

The speeches reiterated the same notion – that they hoped through the Institute, Bendigo men and boys of the Railways service would be able to better improve themselves, generating benefit for both the railway and the community.

The first semblance of the VRI had been established with a library at Spencer Street in 1888, with a dedicated magazine, Railways, published from 1899. On a recommendation made in 1900, the Railways Institute was founded to provide education for employees with a curriculum that would eventually cover construction, telegraphy, safe railway working practices, shorthand, accountancy, ambulance work, building maintenance, general literacy, typewriting, guard duties, engine management, elementary electricity & magnetism, and use of the Westinghouse brake. By 1904, it was up and running, financed by employee fines and matched with railway revenue.

The speeches reiterated the same notion – that they hoped through the Institute, Bendigo men and boys of the Railways service would be able to better improve themselves, generating benefit for both the railway and the community.

The first semblance of the VRI had been established with a library at Spencer Street in 1888, with a dedicated magazine, Railways, published from 1899. On a recommendation made in 1900, the Railways Institute was founded to provide education for employees with a curriculum that would eventually cover construction, telegraphy, safe railway working practices, shorthand, accountancy, ambulance work, building maintenance, general literacy, typewriting, guard duties, engine management, elementary electricity & magnetism, and use of the Westinghouse brake. By 1904, it was up and running, financed by employee fines and matched with railway revenue.

The Flinders Street institute opened in 1910 with over 3,000 members signed up. This facility had a gym, billiards room, tuition and a library of 11,3000 volumes. The first country branch was established at Ballarat in 1916, a time when Bendigo was still grappling with a location for their VRI activities. Several years earlier, the committee had applied to the YMA to lease the top flat of their ‘new’ premises on the corner of High and Short Street but found the figure offered was too high. The vacant lot next to the station on Mitchell Street was soon flagged as a potential site, and though the Commissioners were favourable, on account of the drought, then the War, finances were not available.

Early meetings of the branch took place at the assembly hall at the railway station, with 23 members, each representing a branch of the railways. With fundraising on the sidelines, the committee worked instead on building membership and by the end of 1914, had recruited 200 members. The Trades Hall was used occasionally for classes, which were also open to public servants, but a cap of 100 allowed per annum. Effort was also made into building the library – the Flinders Street collection of 30,000 books was second only to the Melbourne Public Library – and reginal members were able to borrow books, sent up by train of course, two at a time. As well as railway works, manuals and text books, the library also hosted many works of fiction.

Public Record Office Victoria – Victorian Railways VPRS 12903 Photographic Negatives: Railways: Box Systems

‘The stability of a nation more or less depends upon the education of its people’, wrote the Bendigo Independent, and other areas were keen to follow the lead of Ballarat and Bendigo, with plans soon drawn up for a Seymour institute. Tutors remained the local committee’s authority to appoint but the Railways commissioners reserved the right to examine teachers to ensure they were adequately qualified. Some who taught at the Bendigo VRI were also engaged with the Bendigo School of Mines. The Bendigo VRI was able to boast in 1940 that every single one of their engine working class students passed every single subject.

Social activities formed an important part of the VRI, testament to this was the inclusion of a dedicated billiard room – which remains in use for local billiard and snooker clubs today! Billiard halls had been somewhat contentious in Bendigo, with some of the belief that skill in playing billiards was evidence of ‘a wasted, ill spent youth’, and objected to the new YMCA hall in 1908 allowing its practice. In addition to billiards, there were competitions for lawn and carpet bowls, cricket and football. A VRI bowls team also still exists in Bendigo.

Public Record Office Victoria – Victorian Railways VPRS 12903 Photographic Negatives: Railways: Box Systems

There were also dances and concerts across the VRI network – the famous Flinders Street Ballroom was built as part of the VRI. They also took part in smoke socials and the Bendigo railways picnics. As late as the 1950s, the Bendigo VRI Hall was even used for the odd wedding reception!

From the Victorian Railways collection at PROV’s Victorian Archives Centre, we can see that plans existed for the extension of the Hall in Mitchell Street (example below), but they don’t seem to have occurred. Other plans in the collection show floor plans for additions to comply with various Health Department acts. These and more can be seen in our exhibition upstairs at the Bendigo Library (12 October – 30 November).

Public Record Office Victoria – Victorian Railways VPRS 4986 VRI alterations to conform with Board of Health

Still On Track After 160 Years

We hope that this article has demonstrated how some of the records in the BRAC and PROV collections can be used in building a story of community events and the lives of ordinary people in Bendigo, and what sort of information these collections might contain. Our temporary exhibition will be upstairs in the Bendigo Library from mid-October until sometime before Christmas. It features many more photographs, records and ephemera relating to the spaces and people covered in this article. An appendix notes the Public Record Office Victoria items that are included, all of which can be ordered to view in the Reading Room on any open day (Wednesday and Thursday), at the Victorian Archives Centre on weekdays, or online for those records which have been digitised.

There are many elements to Bendigo’s railway story that warrant further exploration:

-

The State-wide First Aid Competitions – who competed, when and why were they implemented, was/is competition a useful way of training, when and why did they conclude, how was training conducted?

-

Victorian Railway Institutes – what was the scale of the VRI’s impact on secondary/tertiary education levels across the state? When and why did the focus change from educational to purely social?

-

Refreshment Rooms – Did they operate the same way as a standard restaurant, and if not, in what ways? How many staff were employed at Bendigo and did they contribute to levels of women’s employment opportunity over time? When did they close, and why?

About BRAC’s Collection

The Bendigo Regional Archives Centre is based in the Bendigo Library with two class A repositories which house thousands of public records from Bendigo and greater north west region. The bulk of the collection consists of council records but also includes records from courts, cemeteries, water authorities, and education institutes. The broader Public Record Office Victoria collection also holds many records relevant to the Bendigo district and the running of the railways. The exhibition and this article draw on both collections as a way of telling lesser known stories of the Bendigo railway but also as a showcase of the type of information that can be found in these collections, and how it can be used.

The records that we have used in putting together this article and the exhibition include Municipal District of Sandhurst Minutes, City of Sandhurst-Bendigo inward correspondence, Bendigo Courts Licence Register, Inquest Deposition Files, Victorian Railways Photographic Negatives, Salary Record Books and architectural plans, and Crown Lands Departments plans.

Roll of Sandhurst-Bendigo Station Masters

1862-1863 Henry Masters BARTER

1863-1865 William CAMERON

1865-1865 John ANDERSON

1865-1870 John O’MALLEY

1870-1888 William Robertson RAMSAY

1888-1890 John Ernest Francis FRANKS

1890-1891 Isaac John CHAPMAN

1891-1893 William George SINCLAIR

1893-1894 David Walkenshaw HUNTER

1894-1896 Simon Frederick SMITH

1897-1909 Joseph Sparrow YATES (died)

1909-1916 John William TAYLOR (died)

1916-1919 William NOONAN

1920-1921 D BROWN

1921-1922 James Frederick BROWN

1922-1923 John Thomas KENNY

1923-1930 Michael McCRAITH (died)

1930-1933 Reginald Joseph BUCK

1933-1935 Charles Leslie WADELTON

1935-? AT GILES

Originally published October 2022

Sources Used

Public Record Office Victoria, VA 2889 Registrar General’s Department, VPRS 24 Inquest Deposition Files, P0000, 1860/879 George Warde Inquest

Public Record Office Victoria, VA 4862 Sandhurst (Municipal District), VPRS 16269 Council Minutes

Public Record Office Victoria, VA 2389 Bendigo (City), VPRS 16936 Inward Correspondence

‘Opening of the Sandhurst Railway’, Bendigo Advertiser, 24 Oct 1862, p1

‘Railway aid sought to initiate campaign’, The Herald, 14 May 1931, p18

‘Railway station catering’, Bendigo Advertiser, 9 Apr 1884, p2

‘Unwilling strikers: railways waitresses to resume work today’, The Argus, 14 Sep 1925, p11

‘On the tracks: A one-stop shop’, Old Treasury Building, accessed Sep 2022,

https://www.oldtreasurybuilding.org.au/lost-jobs/on-the-tracks/victorian-railways-a-one-stop-shop/

VPRS13419 P0001 1 – Dietitian book (Bendigo), noting the quality tests done on milk supplied by local companies, including Hollywood Dairy

VPRS 1437 Bendigo Courts Licencing Register 1897

Public Record Office Victoria, VPRS 12800 Photographic Collection: Railway Negatives: Alpha-numeric Systems

Public Record Office Victoria – Sandhurst (Municipal District) VPRS 16269 Council Minutes

Public Record Office Victoria – Bendigo (City) VPRS 16936 Inward Correspondence

Public Record Office Victoria – Registrar-General’s Department VPRS 24 Inquest Deposition Files

Public Record Office Victoria – Bendigo Courts VPRS 1437 Licensing Court Register

Public Record Office Victoria – Victorian Railways VPRS 4986 Proposed alterations & extension to VRI

Public Record Office Victoria – Victorian Railways VPRS 4986 VRI alterations to conform with Board of Health

Public Record Office Victoria – Victorian Railways VPRS 7882 VRI Bendigo Halls & Theatres

Public Record Office Victoria – Crown Lands Department VPRS 242 Sandhurst Station Footpath Map

Public Record Office Victoria – Victorian Railways VPRS 13703 Salary Record Book

Public Record Office Victoria – Victorian Railways VPRS 17077 Contract for Station Master House

‘Brevities’, Riverine Herald, 9 Mar 1887, p2

‘Bendigo Stationmaster expires in the street’, Bendigo Advertiser, 22 Sep 1916, p6

‘Queens and their attendants at the Convent carnival’, Bendigonian, 21 Sep 1916, p16

VPRS 16936 City of Bendigo Inward Correspondence P0001 37 1 - 15 Jun 1893

VPRS 17077 Contract Files – Department of Railways & Roads P0001 8

‘Railways Institute: New building opened’, Bendigo Advertiser¸ 14 April 1924

‘Victorian Railways Institute’, Bendigo Independent, 21 Jan 1914, p5

‘Bendigo’, The Age, 5 Jan 1940, p12

‘Social gossip’, Riverine Herald, 3 Feb 1951, p2

‘Letter’, Bendigo Independent, 25 Sep 1909